What Yale Law School Taught Me about J.D. Vance

Or: how elite institutions helped create a force aimed at their destruction

In February of 2018, at dinner with friends, I missed a call from a New Haven area code. In the throes of the law school admissions cycle and dimly aware that Yale called people to announce acceptances, I looked up, sputtered something apologetic, and walked outside, phone pressed to my ear and ringing, my coat left behind. Across the street, in a shopping mall parking lot, fluorescent lights threw the falling snow into relief. The ringing stopped. One of Yale’s admissions officers answered and congratulated me. I remember him laughing gently at the babble I offered in reply. We hung up. Standing in a cold I’d finally begun to feel, I dialed my mom and wept.

I was raised by a single parent through much of my adolescence. I’m a first generation college graduate from Youngstown, Ohio, a “blue-collar,” Rust Belt city that stood at the forefront of a then-novel Trumpism. I have a B.A. from Youngstown State, an unsung public school primarily serving the educational needs of the local tri-county area. I’ve experienced a fair bit of familial turbulence I won’t divulge here but which made it into my law school diversity statements, packaged and sold as a tranche of obstacles that engendered in me both persistence and perspective. Higher ed admissions taught me how to narrativize my own life.

Like countless American students, I grew up chock full of ideology. Classified as “advanced” from a fairly young age, I was repeatedly reminded that educational attainment was a moral good, not just a practical one. During my time at YSU, I maintained a 4.0 and stuffed my resume with extracurricular achievements. As graduation approached, I yearned for a more prestigious institutional affiliation. So much of my identity was bound up with meritocratic striving; so much of the world reaffirmed that prime directive. When Yale came calling, my deepest insecurities were assuaged, my most elemental desires satiated. I had made it.

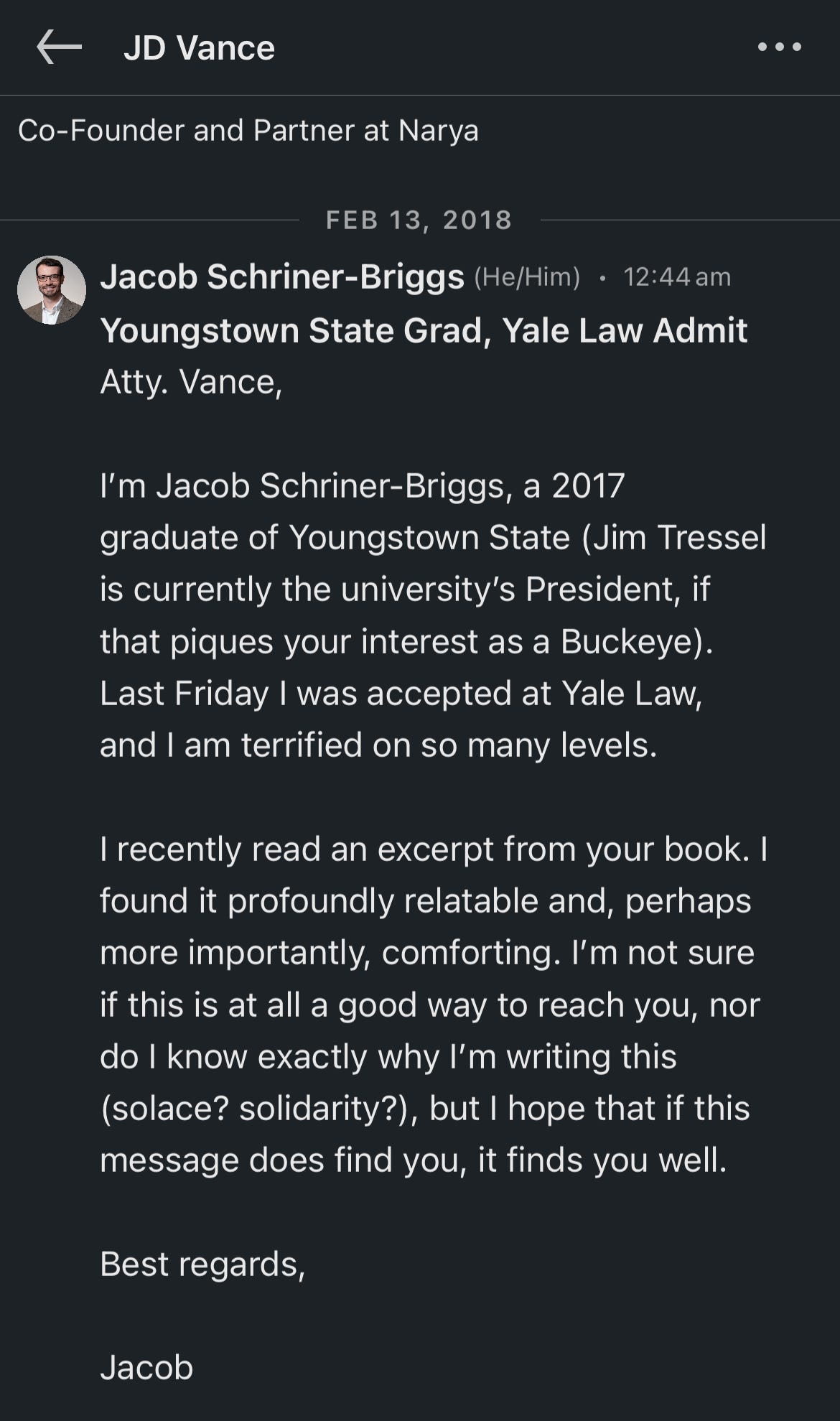

Then the afterglow faded. In its wake, I found I was still myself. Having picked up Hillbilly Elegy at the recommendation of one of my college professors, I did what anyone in my position would: I sent an anxious, oddly sentimental LinkedIn message to J.D. Vance.

The “Good” J.D. Vance

Before he became the Vice President and one of the more odious leaders of a racist and revanchist political movement, Vance was a self-described “communitarian” conservative embraced by the respectable circles of mainstream liberalism. His Yale pedigree compelled myopic political thinkers to take him seriously. And his memoir worked as an act of translation, reassuring highly-educated, well-to-do professionals that the working class, hollowed out by decades of deindustrialization, had only itself to blame.

Boiled down to certain generalities, our biographical profiles are remarkably similar. Vance grew up in Middletown, Ohio; his mother was a nurse; he experienced turbulence at home, went to college at Ohio State as a first gen student, studied philosophy and political science, and attended Yale Law. I grew up in Youngstown, Ohio; my mother is a nurse;1 I experienced turbulence at home, went to college at Youngstown State as a first gen student, studied philosophy and political science, and attended Yale Law.

At a house party near the end of my first semester, a classmate who’d gotten to know me a bit said I was the “good” J.D. Vance and that I’d be the President one day. A well-meaning boost to my fragile ego, it doesn’t take much to see the pernicious dynamics underwriting the exchange. I had a story of hardscrabble resilience I could market; I was a tall, white, straight man;2 I’d gotten into Yale; unlike Vance, my politics were progressive, and so I could pitch myself as the Pepsi to his “Never Trump” Coke. The groundwork for a successful electoral career was self-evident.

Before starting at YLS, I don’t think I’d ever met a Harvard, Princeton, or Yale grad. By the end of orientation, I’d met dozens. I shared space with the children of billionaires, a U.S. Senator, and a Vice President. One day after class, tired and stressed, I did a double take having passed Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan in the hallway.

Despite the unimaginable network power oozing from its every nook and cranny, Yale didn’t propel me toward especially lofty ambitions. My first semester was an alienating experience, a sensation that grew worse with time and which the COVID pandemic supercharged. By the end of my 3L year, I’d become emotionally sick and unmoored. I dealt on and off with depression.

Vance claims to have generally enjoyed his time at YLS, a place he describes as “a nerd Hollywood.” While he admits in Hillbilly Elegy that Yale made him uncomfortable as a socioeconomic outsider, he frames these feelings as pathological vestiges of his upbringing, better outgrown than interrogated. “Mamaw always resented the hillbilly stereotype—the idea that our people were a bunch of slobbering morons,” he writes. “But the fact is that I was remarkably ignorant of how to get ahead.”

The Politics of Hillbilly Elegy and those that Boosted it

The latter parts of Vance’s memoir offer a tasteful and contrived narration of his law school journey. Shepherded by his girlfriend Usha and Professor Amy Chua, Vance learns about etiquette and “networking power.” He learns about the social and emotional scars trauma leaves behind. And he learns how to pursue a healthy and fulfilling life on his own terms.

Hillbilly Elegy is a just so story. In one overwrought anecdote, Usha teaches a bewildered J.D. how to use his many utensils at a law firm recruitment dinner. Later, she helps him navigate his communication struggles within their relationship, challenges stemming from his rough-and-tumble upbringing. For her part, Professor Chua gives Vance a permission structure to forego raw career ambition in favor of his budding life with Usha. “My professor gave me permission to be me.”

Taken on their own terms, these set pieces are unobjectionable, sometimes tender. Yet they sit atop a politics that is by turns cruel and outlandish. Its cruelty lies in its refusal to see the kinds of working class communities from which Vance emerged as comprised of fully formed people subjected to forces beyond their control. “[B]efore anything else,” Gabe Winant explains, “Hillbilly Elegy is committed to the ethic of culpability.” The book’s central argument submits that “hillbilly culture, damaged fatally by lack of personal discipline, lowers expectations for children and thereby causes the intergenerational transmission of poverty.”

The outlandishness of the book’s bootstrap politics is most acute when its refusal to see structural forces comes into direct contact with them. Vance’s experience at Yale lets him meditate on the idea of social capital which he describes as “a measure of how much we learn through our friends, colleagues, and mentors.” This nonsense elides the obvious differences between Vance’s Yale network and the networks people in Middletown or Youngstown can conceivably leverage. In Vance’s world, social capital is all form and no substance, as simple as talking with whichever acquaintances one happens to have nearby.

Vance’s own examples, his personal “education in social capital,” makes the point. In just one paragraph, Vance describes how his relationship with David Frum, a former speechwriter for George W. Bush, generated relationships with two of Frum’s “friends from the Bush administration,” senior partners at a presumably high-powered law firm who then facilitated Vance’s connection with Indiana governor Mitch Daniels.

The lessons Vance takes from this carousel of elite connection? That “social capital is all around us;” that “[t]hose who tap into it and use it prosper;” and that “[t]hose who don’t are running life’s race with a major handicap.” Social capital is a new age force, a $45 crystal with important energies we all can exploit. With just this one trick, you, too, can unlock an introduction to the Bush White House Alumni Group.

In a jaw-dropping passage, Vance writes that

[n]ot knowing things that many others do has serious economic consequences. It cost me a job in college (apparently Marine Corps boots and khaki pants aren’t proper interview attire) and could have cost me a lot more in law school if I hadn’t had a few people helping me every step of the way.

The reason failure to tap into Yale’s social capital could have cost J.D. “a lot more” is both obvious and unmentioned: Yale’s networks are exponentially more powerful than others. That Vance fails to deal at all with this glaring inequality is conscious obfuscation. A young person from Youngstown can use their network much more tactfully and strategically than Vance ever did and yet is unlikely to convince billionaires like Peter Thiel to hand them a job, donate millions to their Senate campaign, and help ingratiate them to Donald Trump.

This combination—the rhetoric of individual responsibility and the refusal to acknowledge structural inequality—runs all throughout Hillbilly Elegy.3 Because the book concedes minimal power to structural explanations, those looking for a cultural understanding of the first Trump election swore by it. Elegy flattered influential sensibilities and was accordingly boosted over and over and over again.

J.D. Vance had a story of hardscrabble resilience he could market. (At the advice of his mentor, he did.) He’s a tall, white, straight man with a working class background and a Yale law degree. His “Never Trump” politics were conservative yet tasteful. The groundwork for a successful electoral career was self-evident. Ever the opportunist, and sensing that the political winds were shifting, Vance cashed in the chips elite institutions had handed him and cut a hard turn right.

Toward a Gentler Tomorrow

The first paragraph of this essay is nearly identical to the first paragraph of a 2L term paper I wrote over five years ago. The narrativization of my own life, the reduction of complicated factors to a comfortable stock story, comes naturally now.

I titled the paper Toward a Gentler Tomorrow. It was a blend of argument and memoir. Under the guidance of one of my own YLS mentors, I wanted to test both my academic and literary chops. My mentor agreed that it could be a book project, public facing, a response to Vance’s cynical individualism. I was intoxicated by the idea—if not the President, I, too, could be a media darling with important political insights to offer.

A subsequent phone call broke the fever. Like Chua did for Vance, my mentor pressed me kindly but firmly on whether my stated desires were genuine. They weren’t. There were things I needed to say to sell my story, family I’d need to sell out. I couldn’t do it.

My mentor gave me a permission structure, too. It was alright. I didn’t need to commodify myself anymore. I didn’t need to sell my story. None of this answered the question of what I should be doing, but it let me stop striving, take a beat, breathe, think.

In 2018, I sent a direct message to “Atty. Vance.” Laughable in hindsight, I didn’t know how to leverage networks even though, as a newly-minted “Yale Law Admit,” I now had one to leverage. I wanted “solace” or “solidarity” at a time I was realizing inchoately something I now understand completely. Yale could drastically improve my material prospects, the most consequential contingency of all, but it would never resolve the existential anxieties to which my own traumas had contributed.

I’d love to be a teacher and scholar, and I’m working hard toward that end. Yet nothing is guaranteed, and I worry what will happen if I fail. Failure would cut deep. It would threaten my sense of self which, despite my best efforts, remains informed by a deep desire for meritocratic approval. My hope is that failure, should it happen, would prompt me to act on what I know: that people can care for each other and make new meanings together. That “failure” in this sense is a meaning better left behind. That solidarity and solace abound if you know where to look.

I was never going to find those things in J.D. Vance. No longer the clean-shaven “hillbilly whisperer,” he’s since endorsed a conspiratorial politics of schadenfreude, targeting vulnerable groups like the trans community and Haitian immigrants as well as the elite institutions that failed to provide the care and safety his childhood denied him.

I don’t know what this political moment will yield. But if Yale Law School taught me anything, even if by negative example, it’s that we should strive for a gentler politics than the individualism and recriminations of J.D. Vance.

I’ve thought about our similarities before, but hadn’t previously appreciated that both our mothers worked as nurses, a fact which reminded me of historian Gabe Winant’s book The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America. Coincidentally, Winant wrote an essay on J.D. Vance in 2023 which, for my money, is the best of a crowded genre.

Vance makes this same disclaimer in Hillbilly Elegy: “I lived among newly christened members of what folks back home pejoratively call the ‘elites,’ and by every outward appearance, I was one of them: I am a tall, white, straight male. I have never felt out of place in my entire life. But I did at Yale.”

Read with the knowledge of Vance’s subsequent political trajectory, Elegy is a remarkable text. Take the above passage alone. Vance either ignores or fails to understand that many of his classmates were not “newly christened” elites but had been elites since birth and that “elite” can take on a dual meaning that is simultaneously pejorative and descriptive. He now excoriates the same social and economic class he so badly wanted to accept him. Most astonishingly, Vance implicitly admits of identity-based privileges, quite the departure from now-Vice President Vance who cynically and baselessly intimated that an airplane crash killing 67 people was caused by “diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

The book is full of examples of this phenomenon. In chapter 9, Vance criticizes the working class for eating processed foods without considering the structural fact of food deserts or the intentionally addictive qualities of the “Pillsbury cinnamon rolls” he slams poorer communities for consuming. In chapter 11, he defends payday lenders as a solution for precarious working class people with bad credit, failing to ask why so many are precarious or have bad credit in the first place let alone whether it’s conscionable for payday loans to impose arrestingly predatory interest rates.

I trashed Vance's book on Amazon in 2019 and declared it to be Reader's Digest material. Vance was a self-serving hypocrite then and he's worse now. I recall his nasty reaction to the guy in one of his classes at Ohio State with the scraggly beard he deemed idiotic or ill-informed and by then I knew, from that and other evidence in the book, that he was a bigot, a tribalist and an opportunist who didn't appreciate his good fortune at all.

He's now both a rich Social Darwinist and a religious nut so he straddles the two elements that make up the Republican coalition in an unusual way, and his conversion to Catholicism makes him more of a rare form of sleaze, the evangelicals having farmed out the intellectual heavy lifting at the Supreme Court level to Franco-authoritarian Catholics because they're apparently incapable of producing such people in-house. Vance seems to think he knows better than the people who wrote the Constitution AND the pope so it will be interesting to see how it plays out if Trump drops dead. It will be interesting to see how it plays out in any case, but watching him crush his own soul and become a certified shill for the apocalypse has been a disturbing and disgusting spectacle.

Well, that is an excellent account of a young man coming to grips with some deep soul searching (philosophy can run hot and cold) in a crowded room of whip smart ambition.

Social capital ain’t worth a hill of beans if you can’t stand hanging out with them it at the pub.

Plenty of room in the world for well educated decency. Make yourself useful to those that need a leg up from someone who can help. Always a good idea to remember humanity is like being in a band, music sounds better if everyone practices.

You will have far less sleepless night.

Thanks for the essay, I enjoyed reading it.